Five key takeaways from the ICJ’s historic climate ruling and what comes next

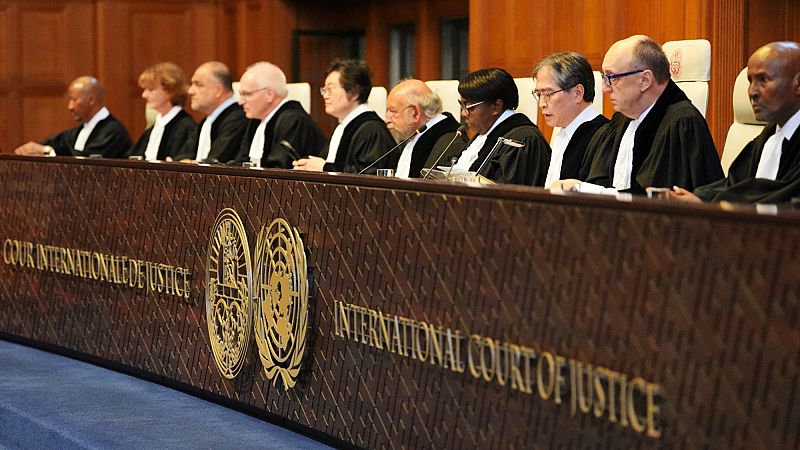

On Wednesday, the UN’s highest court delivered a historic opinion on climate change, outlining states’ responsibilities under international law.

It was the largest case ever seen by the International Court of Justice (ICJ), with more than 150 submissions from states, international organisations, and civil society groups. Over 100 states and international organisations took part in hearings last December.

The ICJ is the world’s highest court, but its 133-page advisory opinion is not legally binding. Although it doesn’t establish new international laws, it clarifies existing ones and is likely to be cited in future climate litigation and UN negotiations like COP30 in Brazil later this year.

Experts believe it could have a plethora of consequences for global climate action. But what do the key parts of the ICJ’s advisory opinion actually mean?

A healthy environment is a human right

The ICJ affirmed that a “clean, healthy and sustainable environment” is a human right, just like access to water, food and housing.

In 2022, the UN General Assembly adopted a resolution acknowledging this right. The ICJ confirmed this again on Wednesday, saying that a clean, healthy and sustainable environment is foundational for the effective enjoyment of all human rights.

It means that, as Member States are parties to numerous human rights treaties, including the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, they are required to guarantee the enjoyment of such rights by addressing climate change.

Preventing climate harm is bigger than the Paris Agreement

Big emitters were accused of trying to hide behind the Paris Agreement during the hearings for the case. In December, they argued that the international climate agreement was already a sufficient framework that outlined states’ climate responsibilities.

But the court confirmed that climate change threatens human rights and involves multiple branches of international law, from international human rights law to environmental law and the UN Charter, not just the Paris Agreement.

This means any duty to prevent harm to the environment and protect the climate applies to all states, whether or not they are parties to specific UN climate agreements.

The ICJ also emphasised the need for ambition and accountability, not merely having a plan.

Nationally Determined Contributions or NDCs are national climate plans that represent each country's commitment to reducing greenhouse gas emissions and adapting to the impacts of climate change. They are a core part of the Paris Agreement.

The content of each country’s NDC is as relevant to whether they are complying with their legal obligations as simply submitting one. Essentially, it means any plan must be ambitious and in line with climate science, reflecting a state’s “highest possible ambition”, and must become “more demanding over time”.

States that fail to act on climate change risk are breaking the law

“Failure of the state to take appropriate action to protect the climate system from GHG (greenhouse gas) emissions … may constitute an internationally wrongful act which is attributable to that state,” Court president Iwasawa Yuji said. He specifically mentioned fossil fuel production and consumption, as well as the provision of subsidies.

This means countries that fail to take measures to protect the planet from climate change could be in violation of international law. If governments and parliaments fail to curb the production and consumption of fossil fuels, approve fossil fuel projects and roll out public money for fossil fuels, they could also be in breach of international law.

The court also confirmed that countries are bound by international law to regulate the climate impact of businesses and companies within their jurisdiction, including fossil fuel firms.

States harmed by climate change have a right to seek reparations

The court affirmed that legal consequences for climate harm include restitution, compensation and guarantees of non-repetition. That means states responsible for unlawful emissions could be required to stop harmful actions, restore damaged infrastructure or ecosystems - or provide financial compensation for the losses suffered.

The ruling paves the way for vulnerable nations to seek reparations from historical emitters for the harm they have endured from climate impacts like extreme weather. In other words, they could sue high-emitting nations, including for past emissions.

“If states have legal duties to prevent climate harm, then victims of that harm have a right to redress,” explains Sebastien Duyck, senior attorney at the Centre for International Environmental Law.

“In this way, the ICJ advisory opinion not only clarifies existing rules, it creates legal momentum. It reshapes what is now considered legally possible, actionable, and ultimately enforceable.”

The ICJ’s opinion could affect current climate cases and future agreements

The ICJ’s opinion opens the door for other legal actions, from states returning to the ICJ to hold each other accountable to domestic lawsuits.

“This newfound clarity will equip judges with definitive guidance that will likely shape climate cases for decades to come,” says ClientEarth lawyer Lea Main-Klingst.

“And outside the courtroom, this result is a powerful advocacy tool. Each and every one of us can use this decision to demand our governments and parliaments take more ambitious action on climate change to comply with both the Paris Agreement and other applicable international laws.”

That includes in the lead-up to and during upcoming negotiations at COP30, where the advisory opinion from the ICJ could be used as leverage.

Yesterday