Billionaires, frequent flyers, oil and gas: Who could fund COP29’s $1tn finance target?

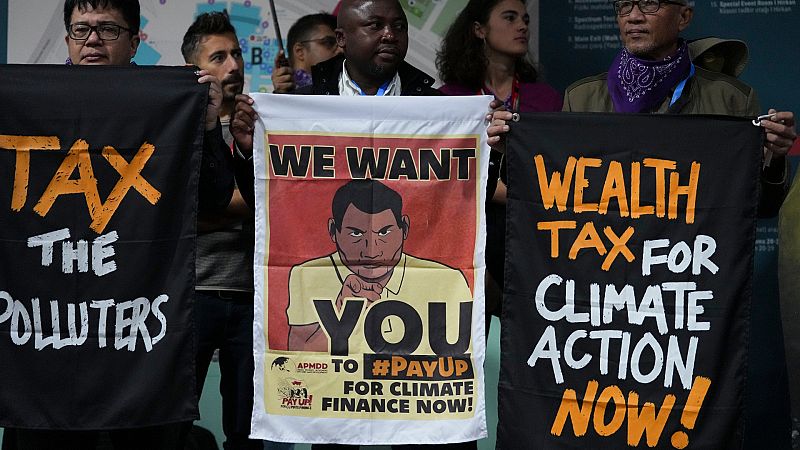

Who should foot the climate finance bill - from loss and damage funds to new funding targets - has become an enduring controversy at recent COPs.

Experts have said that at least $1 trillion (€948 billion) needs to flow to developing nations by 2030 and a new climate finance goal known as the new collective quantified goal (NCQG) hangs in the balance in Baku.

Rich countries are calling for the pool of contributors to be widened. As developing nations deal with the growing frequency and scale of climate disasters, the urgency for these funds increases.

There are big gaps that rich nations will need to fill with innovative forms of finance. From levies on high carbon activities to wealth taxes, what are some of the alternative ideas on the table for raising this cash?

Simple solutions or difficult diplomacy?

A study published by civil society group Oil Change International in September found that rich countries could raise five times the money developing nations are demanding in climate finance with a series of what it calls “simple measures”.

According to the study, a combination of wealth and corporate taxes, taxes on fossil fuel extraction and a crackdown on subsidies could generate $5 trillion (€4.7 trillion) a year - five times what developing nations say they need.

Stopping fossil fuel subsidies alone could free up $270 billion (€256 billion) in rich countries and a tax on fossil fuel extraction could raise $160 billion (€152billion). A frequent flyer levy could total $81 billion (€77 billion) a year from the rich world and increasing wealth taxes on multimillionaires and billionaires would raise a staggering $2.56 trillion (€2.43 trillion). In total, the list of measures it proposes would raise $5.3 trillion (€5.02 trillion) a year.

Some of these options are likely to be easier to implement than others. While adding a levy for frequent fliers doesn’t seem that controversial, money talks and strong opposition from billionaires could stop a wealth tax in its tracks.

Another proposal, redistributing 20 per cent of public military spending to raise $260 billion (€246 billion), could also prove tricky in a world of growing geopolitical instability.

Could a billionaire tax help pay the climate finance bill?

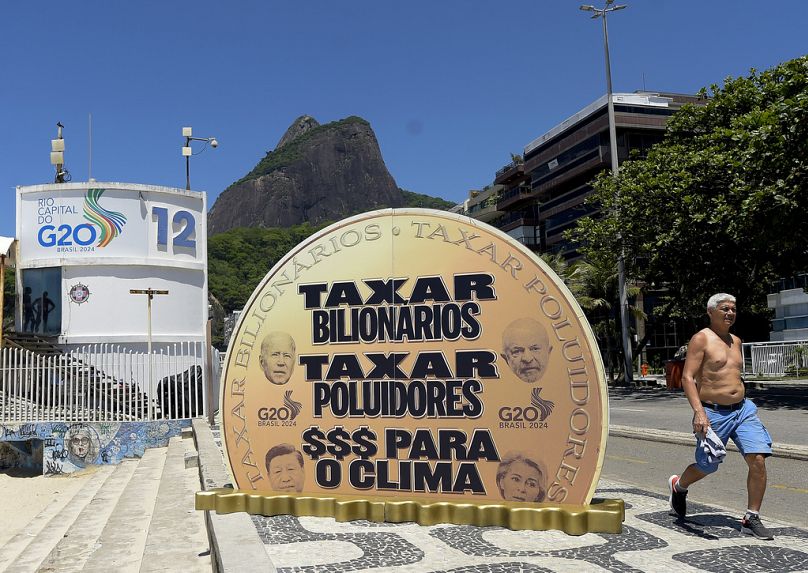

In July, a meeting of G20 finance ministers in Rio agreed to a "dialogue on fair and progressive taxation, including of ultra-high-net-worth individuals”. Brazilian President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva is hoping to progress talks on this potential billionaire tax at the G20 meeting this week.

The baseline proposal from the finance ministers of Brazil, Germany, Spain and South Africa earlier this year recommended a 2 per cent tax on roughly 3,000 individuals with a net worth of more than $1 billion (€946 million). This would raise around €230 billion a year to fight poverty, inequality - and the climate crisis.

It has broad public support in G20 nations with an Ipsos poll from June showing that 70 per cent of people back the idea that wealthy people should pay higher income tax rates. But as G20 leaders meet in Brazil this week, there are reports that negotiators from Argentina’s new right-wing government are trying to undo progress made on this agreement.

“There is huge popular support in the G20 countries for a tax on the super-rich and it is important that the European countries in the G20 rally behind the Brazillian President to protect the unprecedented agreement on taxing extreme wealth achieved by the finance ministers in July,” says Kate Blagojevic, associate director of Europe campaigns at 350.org.

“It makes common sense to tax mega polluters and the mega-rich to ensure that we have the money needed for climate action at home and globally, which can prevent and repair damage from extreme weather like we have seen in Spain and in Central America over the last few weeks.”

Other countries have not been keen to criticise the proposal in public but many fear that announcing such a tax would cause these ultra-wealthy individuals to flee to nations with more attractive tax policies.

Spain's economy minister Carlos Cuerpo urged countries on Monday before the G20 meeting to "be brave" and "do things that you are convinced are right".

Could taxing big oil help pay the climate finance bill?

A small tax on just seven of the world’s biggest oil and gas companies would grow the UN’s Loss and Damage fund by more than 2,000 per cent, according to a new analysis published today by Greenpeace International and Stamp Out Poverty.

It says that introducing what it calls a Climate Damages Tax across OECD countries could play an essential role in financing climate action. This is described as a fossil fuel extraction charge applied to the carbon dioxide equivalent emissions of each tonne of coal, barrel of oil or cubic metre of gas produced.

A tax starting at $5 (€4.74) - and increasing year-on-year - per tonne of carbon emissions based on the volumes of oil and gas extracted by each company would raise an estimated $900 billion (€853 billion) by 2030, it finds. The two groups say this money would support governments and communities around the world as they face growing climate impacts.

“Who should pay? This is fundamentally an issue of climate justice and it is time to shift the financial burden for the climate crisis from its victims to the polluters behind it,” says Abdoulaye Diallo, co-head of Greenpeace International’s Stop Drilling Start Paying campaign.

Diallo adds that the analysis lays bare the scale of the challenge posed by the requirement for loss and damage funding “and the urgent need for innovative solutions to raise the funds to meet it”.

Could taxing frequent fliers help Europe raise climate finance funds?

In Europe, a tax on frequent fliers could raise €64 billion and slash emissions by a fifth, according to a report from environmental campaign groups Stay Grounded and the New Economics Foundation (NEF) published in October.

Currently, regardless of how many times a year you fly, you pay the same amount of aviation tax. But the report proposes an increasing level of tax for each flight a person takes in a year.

It would be added to all trips departing from the European Economic Area (EEA) and the UK, excluding the first two journeys. There would also be a surcharge on the most polluting medium and long-haul flights as well as business and first-class seats.

For the first and second flights taken in a year, a €50 surcharge would be applied to medium-haul and €100 to long-haul, business and first-class flights. For the third and fourth flights, a €50 levy would be added to every ticket plus an additional €50 surcharge for medium-haul and €100 for longer distances and comfort classes.

For fifth and sixth flights, the levy would rise to €100 per flight, plus the additional surcharges. For seventh and eighth flights the levy would be €200, rising to €400 for every flight thereafter.

In a way, this is also a kind of wealth tax. Five per cent of households earning over €100,000 take three or more return flights a year versus just 5 per cent of households earning less than €20,000.

A portion of these funds, according to senior researcher at NEF Sebastian Mang, should be ringfenced for the EU’s contribution to lower and middle-income countries dealing with the sharp end of the climate crisis.