'The future is in our hands’: Climate scientists share solutions as 2024 declared hottest on record

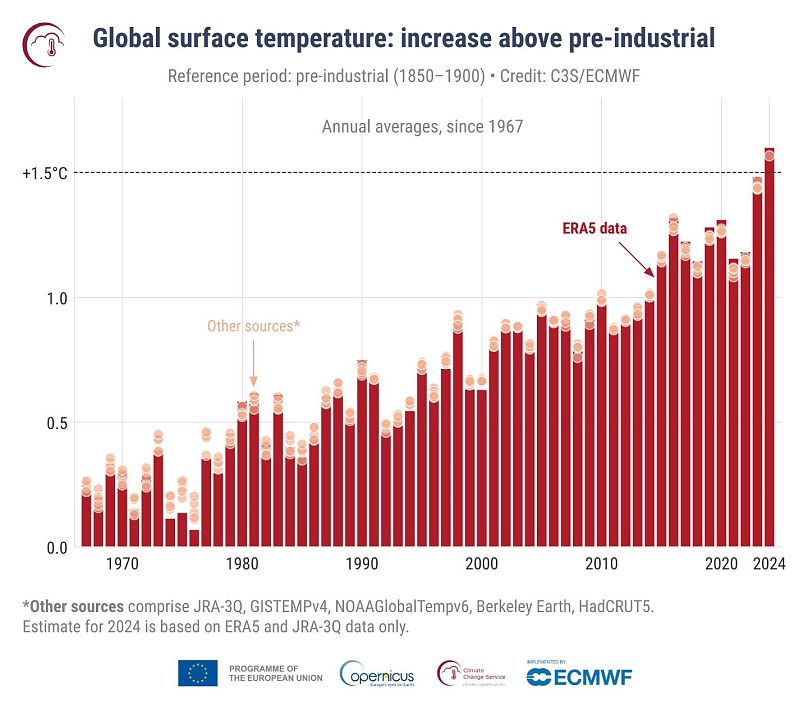

2024 was the warmest year on record and the first calendar year where the global temperature exceeded 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, according to the Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S).

Scientists had suspected 2024 would clinch the record and now it has been confirmed.

Each of the last 10 years - from 2015 to 2024 - was one of the 10 warmest on record, according to the EU climate monitoring service. Its 2024 Global Climate Highlights report outlines the exceptional conditions the world experienced last year.

“We are now teetering on the edge of passing the 1.5ºC level defined in the Paris Agreement and the average of the last two years is already above this level,” says Samantha Burgess, strategic lead for climate at the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts.

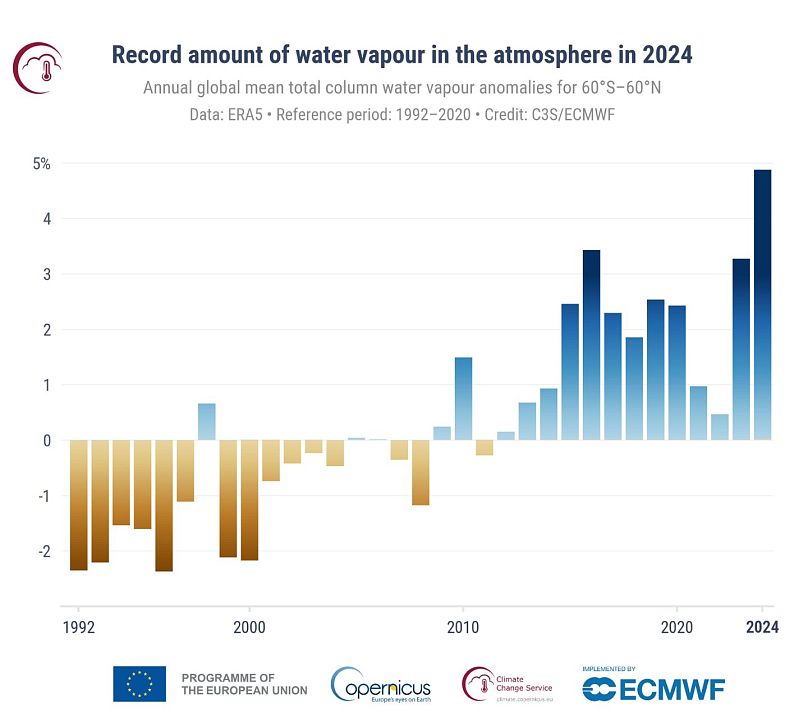

“These high global temperatures, coupled with record global atmospheric water vapour levels in 2024, meant unprecedented heatwaves and heavy rainfall events, causing misery for millions of people.”

Europe saw extreme weather sweep the continent throughout the year, with hundreds of lives lost in disasters like the Valencia floods, Storm Boris and sweltering summer heatwaves in the Mediterranean.

What does this mean for the 1.5C Paris Agreement limit?

The report confirms that last year was the first year where temperature averages exceeded 1.5°C above pre-industrial times. The two-year average from 2023 to 2024 also exceeds this threshold.

The limit set by the Paris Agreement refers to temperature anomalies averaged over at least 20 years so this hasn't yet been broken. The data, however, underscores that global temperatures are now rising beyond what modern humans have ever experienced before.

“Hopefully that is really a wake-up call for humanity,” says professor at the Department of Environmental Sciences and Policy, Central European University and Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) vice chair Diana Urge-Vorsatz.

Currently, the IPCC believes we’ll exceed the Paris Agreement limit around the early 2030s.

“There is a very intense debate going on among the climate scientist community about whether global warming is accelerating or not due to these really extreme temperatures in the last two years,” Urge-Vorsatz notes.

Temperatures didn’t return to the “old normal” after the El Niño climate phenomenon ended in May last year like scientists expected they would. Instead, 2024 went on to exceed the 2023 heat record.

Some have theorised that a reduction in air pollution may have been reflecting solar radiation and masking the true extent of global warming. Global warming itself might be reducing low-level cloud cover causing temperatures to rise.

A multitude of other factors that play a role in our complex global climate system could also be to blame for what appears to be an acceleration in warming.

On the other side of the debate, scientists see this “blip” as falling within projections for global warming.

“A lot of scientists do feel that actually the previous climate models still fully explain this,” Urge-Vorsatz says.

“There is no consensus on this yet,” she emphasises.

“We will only know in a few years whether this was just a natural variability blip or it is due to some phenomena that we have not yet understood.”

Did record temperature fuel 2024’s deadly weather?

Last year brought a plethora of deadly extreme weather events around the world from severe storms to flooding, drought, heatwaves and wildfires. As these events become increasingly frequent and intense, people’s lives and livelihoods across the globe are threatened.

In 2024, the total amount of water vapour in the atmosphere reached a record high - around 5 per cent higher than the average from 1991 to 2020 and significantly higher than in 2023.

“The majority of the excess heat that we have been trapping as a result of the greenhouse effect and human activities has been absorbed by the oceans,” says Urge-Vorsatz, "and ocean heat content has been increasing very alarmingly."

“Hotter sea surfaces are able to evaporate more so that means that as a result, we are seeing higher humidity levels and higher water vapour.”

The unusually moist atmosphere amplified the potential for extreme rainfall and, combined with high sea surface temperature, contributed to the development of major storms including tropical cyclones.

This doesn’t mean more precipitation everywhere but does mean more intense rain where it does fall and even drought in other parts of the world as the water cycle becomes more extreme on both ends of the scale.

"Soaring global temperatures and record water vapour levels in the air only promise more extreme, more frequent and more erratic weather stripping people of their access to life-saving clean water, sanitation and hygiene," says Helen Rumford, lead policy analyst for climate at WaterAid UK.

"We must take action now to protect the most vulnerable in the face of escalating uncertainty and prioritise investment in these basic human essentials. Millions of lives are on the edge of catastrophe."

Prolonged periods of dryness in some parts of the world also created conditions conducive to wildfires.

The Americas were the most affected continents. Large and persistent blazes were recorded last year across south Brazil and Bolivia from August to October and in Canada during July and August.

Fire carbon emissions were the highest on record for Bolivia and Venezuela, and Canada ranked second after 2023, according to data from the Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service (CAMS).

“The signs couldn’t be clearer: as LA continues to burn, the world broke through the 1.5C temperature rise threshold over the whole of 2024," says Champa Patel, executive director for governments and policy at the non-profit Climate Group.

"Despite all the denials, this is what climate reality looks like."

High temperatures can have deadly consequences

High temperatures themselves are a danger. Alongside other environmental factors like humidity, they can stress the body through overheating in a way that can be lethal.

More humid air means we struggle to get rid of excess heat through sweat evaporating off of our skin. This combination of deadly heat and humidity could impact up to 3.5 billion people on the planet by 2070 according to some research.

C3S says that last year, much of the globe experienced more days than average with at least ‘strong heat stress’. Some regions also saw more days than average with ‘extreme heat stress’, at which level actions must be taken to avoid heat stroke.

“Every fraction of a degree matters, because even with this slight increase, we already see that the world is getting more exposed to heat stress,” says Urge-Vorsatz.

We are reaching the limits of adaptation in many areas as with temperatures where our bodies struggle to get rid of heat. And switching on the air conditioning isn’t an option for many faced with these extremes - especially those in the Global South.

Are we doing enough to stem global warming?

“We are doing a lot already, but we need to do more and be more ambitious in more areas,” Urge-Vorsatz says.

Europe, for example, has been very successful in upscaling renewable energy like wind and solar in just a decade or so.

"Well-thought climate action also produces numerous side benefits: we can see the renewable energy revolution already spreading across Europe," says European Green Party co-chair Vula Tsetsi.

Tsetsi adds that Europe has seen substantial progress in green legislation over the last decade and that momentum needs to be maintained.

"This is a moment of choice. Will Europe’s leaders take decisive action, or will they allow the crisis to spiral further?"

Since the Paris Agreement, the world has already avoided the worst-case warming scenarios.

“We no longer expect that the world could warm 5 to 6 degrees by the end of the century, which is a really big deal because when we agreed on the Paris Agreement, these were all potentially possible or just plausible scenarios,” Urge-Vorsatz says.

“Humanity is in charge of its own destiny but how we respond to the climate challenge should be based on evidence," adds Carlo Buontempo, director of C3S.

"The future is in our hands - swift and decisive action can still alter the trajectory of our future climate.”

We still aren’t doing enough. Our hunger for energy is growing faster than we can deploy renewable sources, electric vehicle uptake is slower than needed and fossil fuels aren’t being phased out fast enough.

"2025 has to be the year of concrete, real world climate action that drives immediate results and pushes nations to become electro states," Climate Group's Patel says.

"We need to break down policy and regulatory barriers to unleash renewables and drive down coal use and methane emissions, we need ambitious national climate action plans that are detailed and well-funded, and we need the finance to help people adapt to the devastating impacts of climate change."

The plethora of extreme weather in 2024 served as an ever-present reminder about the importance of adapting to these devastating impacts. In Europe, deadly events over the last few years have been a wake-up call about preparedness for extreme flooding, storms, drought and heatwaves.