One of the world’s oldest icebergs is on the move - and may collide with a wildlife haven

In what sounds like a potential plotline for Speed 3, one of the world’s biggest icebergs is on course to crash into a remote British island, threatening its wildlife and potentially altering its ecosystem.

The mega-iceberg, known as A23a, is currently 280km away from the British territory of South Georgia - home to seabirds, elephant and fur seals, and King and Emperor penguins. But icebergs are unpredictable and it’s unclear how soon this one could hit the island or if it will disintegrate before impact.

In 2004, the island was hit by a smaller iceberg, the A38, causing penguin chicks and seal pups to starve to death on beaches, after their routes to food were blocked by enormous chunks of ice.

How was this giant iceberg formed?

One of the world’s oldest icebergs, and its largest, A23a is double the size of Greater London and weighs nearly a trillion tonnes. It broke off from Antarctica’s Filchner Ice Shelf in 1986 and then got stuck on the seafloor for almost 30 years. After breaking free in 2020, it surprised scientific observers by getting trapped in an oceanic vortex, a phenomenon that keeps objects spinning in place.

In December, A23a spun free of the vortex and has since been on the move through what ecologists call ‘iceberg alley’ located between the continent of Antarctica and the Joinville Island Group. Scientists predict its journey will follow the Antarctic Circumpolar Current into the Southern Ocean, driving it straight to South Georgia.

Just how big is a big iceberg, really?

South Georgia itself is around 170km long and only 35km wide - but it’s not actually going to be hit by something that’s currently the size of Cornwall (3,562 sq km).

A23a measured 3,900 sq km when it first calved – the term for the formation of icebergs when they break off from glaciers – but, as it travels through the warmer waters north of Antarctica, it will begin to melt and chunks of ice will break off.

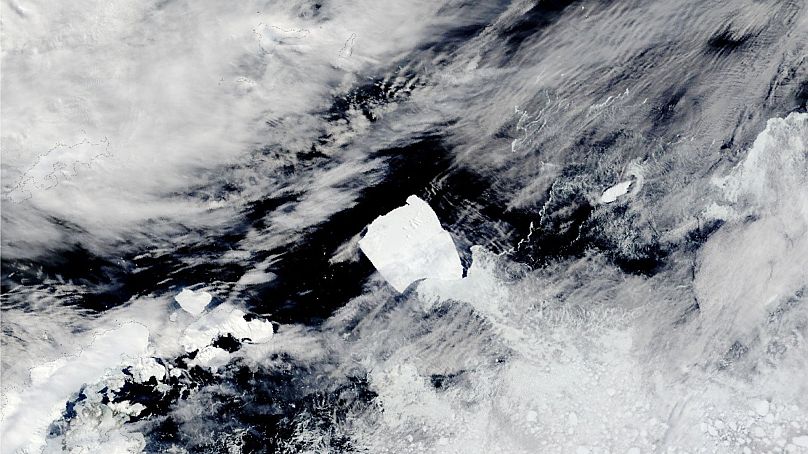

Though smaller, the iceberg will still pack a punch if it collides with the island. Its ice cliffs are up to 400m high (taller than the Shard building in London) and recent NASA satellite images show the vast iceberg is visible from space.

Like everything else, is this to do with climate change?

The UN General Assembly has declared 2025 the year of the glacier, with World Glacier Day landing on 21 March. With glaciers under threat of melting from warming ocean and air temperatures, it’s likely we’ll see more mega icebergs in the future.

But A23a was created long before the recent years of extreme overheating, so climate change can’t be blamed for its formation or why it’s on the move now. Locals report, however, that icebergs are posing an increasing threat.

In 2023, the A76 iceberg came close to grounding in South Georgia. Chunks of the ice that broke off still litter the island, some the size of several Wembley Stadiums.

Icebergs aren’t necessarily a Titanic-scale disaster

The British Antarctic Survey (BAS) co-leads the project OCEAN:ICE, which aims to understand how ice sheets affect the ocean. The project’s co-lead, oceanographer Dr Andrew Meijers, says, “It’s exciting to see A23a on the move again after periods of being stuck. We are interested to see what impact this will have on the local ecosystem.”

A year ago, researchers aboard a BAS research vessel studied the iceberg up close during a mission to understand how Antarctic ecosystems and sea ice influence global ocean cycles of carbon and nutrients.

Laura Taylor, one of the mission’s biogeochemists, explains, “We know that giant icebergs can provide nutrients to the waters they pass through, creating thriving ecosystems in otherwise less productive areas. What we don’t know is what difference particular icebergs, their scale, and their origins can make to that process.”

“We took samples of ocean surface waters behind, immediately adjacent to, and ahead of the iceberg’s route,” adds Taylor. “They should help us determine what life could form around A23a and how it impacts carbon in the ocean and its balance with the atmosphere.”

Yesterday