Could Gaza’s ceasefire process draw lessons from Northern Ireland’s path to peace?

As Palestinians and Israelis wait to see what comes after the ceasefire in Gaza, some are looking to Northern Ireland’s peace process in the 1990s for lessons on how to move from war to peace.

Two figures from that process, former Prime Minister Tony Blair and his former chief of staff Jonathan Powell, are back in the spotlight as they are involved in talks with the United States and other countries about Gaza’s future.

Prime Minister Keir Starmer said this week that “drawing on our experience in Northern Ireland, we stand ready to play a key role in the decommissioning of Hamas’ weapons and capability.”

During “the Troubles,” around 3,600 people were killed and 50,000 wounded in three decades of violence over Northern Ireland’s status. A peace deal, the Good Friday Agreement, was finally signed in 1998. It ended most of the fighting and led to the disarming of the Irish Republican Army (IRA) and other militant groups.

The Trump-backed plan for Gaza is much narrower. It does not deal with the wider Israeli–Palestinian conflict which began decades before the latest war. It doesn't offer a path either to Palestinian statehood, something Israel rejects but that is seen internationally as the only way to resolve the conflict.

The plan calls for Hamas to disarm, something the group refuses to do, though it says it might hand some weapons to a Palestinian or Arab authority.

In Northern Ireland, the IRA’s refusal to give up its weapons was a major problem that threatened the peace process.

Experts say there are similarities, but also major distinctions, between the Northern Ireland conflict and the devastating war in Gaza, which was sparked by Hamas’ 7 October attack on Israel, in which 1,200 people were killed and 251 taken hostage.

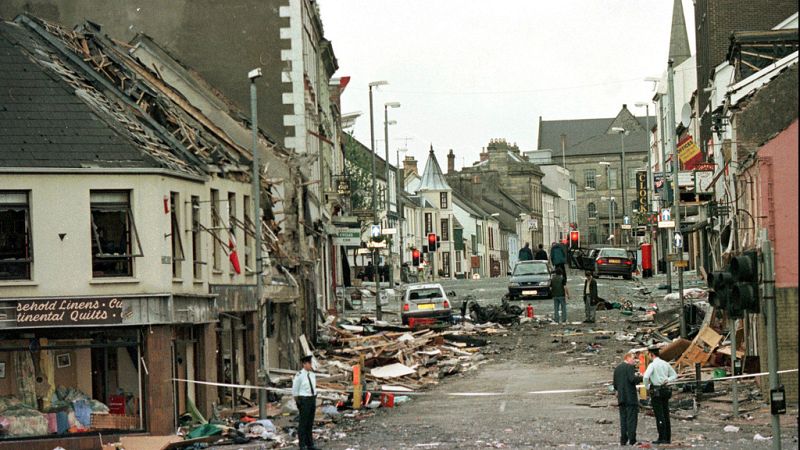

Israel's retaliatory offensive has reduced much of Gaza to rubble, led to famine and killed nearly 68,000 Palestinians, according to the local authorities.

Kristian Brown a politics lecturer at Ulster University in Belfast, said “The level of challenge in the Middle East now is monumental,” adding “The level of bitterness, the sense of immediate threat and the levels of destruction (in Northern Ireland) were not as cataclysmic as Gaza.”

The Irish Republican Army eventually agreed to put its arsenal “beyond use” through a secret process monitored by an international group. This happened while political talks were under way to settle the main disputes, something that more than three decades of US-led peace efforts in the Middle East have failed to accomplish.

In Northern Ireland, disarmament was slow. The IRA began giving up its weapons in 2001 and finished in 2005, seven years after the peace deal. Several other British loyalist and Irish republican militant groups also disarmed as part of the process.

“The British might be able to counsel patience and pragmatism,” said Niall Ó Dochartaigh, a professor of political science at the University of Galway. “The IRA leadership had to be helped in various ways to make that argument (for disarmament) within the organisation.

“Ultimately, decommissioning only happened in the Irish case once the IRA was satisfied that there was a political settlement bedded down,” he added. And while “the contours of a compromise settlement emerged quite early in Northern Ireland,” a similar consensus in the Middle East appears far off.

Fragile power-sharing

The 20-point plan for Gaza includes steps from ceasefire to reconstruction but leaves big questions unanswered, such as the future of Jerusalem, the return of Palestinian refugees, security arrangements, future borders and the scores of Israeli settlements and violence in the occupied West Bank.

The Good Friday Agreement was clearer, setting up a local government and power-sharing system. But even that peace has faced challenges, with occasional attacks and political crises over the years.

Despite this, Northern Ireland remains mostly peaceful. Parties once linked to violence, like Sinn Féin, now play major political roles.

According to Peter McLoughlin, a senior lecturer in politics and history at Queen’s University Belfast, the key to success of Northern Ireland's peace process was "Engaging those involved with violence and bringing them down democratic paths”.

He said excluding Hamas, which has ruled Gaza since 2007, in the future of the strip, could be a problem.

“If there was a broad lesson from the success of Northern Ireland, it’s that an inclusive process worked – and I mean inclusive in the full sense, all different parties, even including militants," McLoughlin said.

“Hamas is being excluded from the political process and is expected to give up its weapons," he added. “I don’t know how feasible that is.”

The return of key players

Tony Blair is seen as possible advisers for Gaza by Trump. Blair, prime minister from 1997 to 2007, also served as envoy to Israel and the Palestinians for the “Quartet”: the US, EU, Russia and UN. But he remains controversial for backing the Iraq War in 2003 and Trump has acknowledged that Blair might not be “an acceptable choice to everybody” in the region.

Meanwhile Jonathan Powell, Starmer’s national security adviser, who attended recent talks in Egypt was praised by US Middle East special envoy Steve Witkoff for “incredible input and tireless efforts” in reaching the agreement.

But Bronwen Maddox, the director of Chatham House, the UK-based international affairs institute, was skeptical about drawing parallels between the two processes. She said Britain “can play a small diplomatic part” in Gaza, but probably not a decisive one.

The Northern Ireland peace deal “was a successful and really important peace negotiation," she said. "But it was very much of itself, I think.”

Today