History's first pandemic: Ancient DNA solves mystery of what caused 1,500-year-old epidemic

In an extraordinary breakthrough, scientists have traced the deadly bacterium behind the world’s earliest recorded pandemic to its epicentre for the first time.

The Justinian Plague, which devastated the eastern Mediterranean 1,500 years ago, has long been described in historical texts - but until now, the microbe responsible remained a mystery.

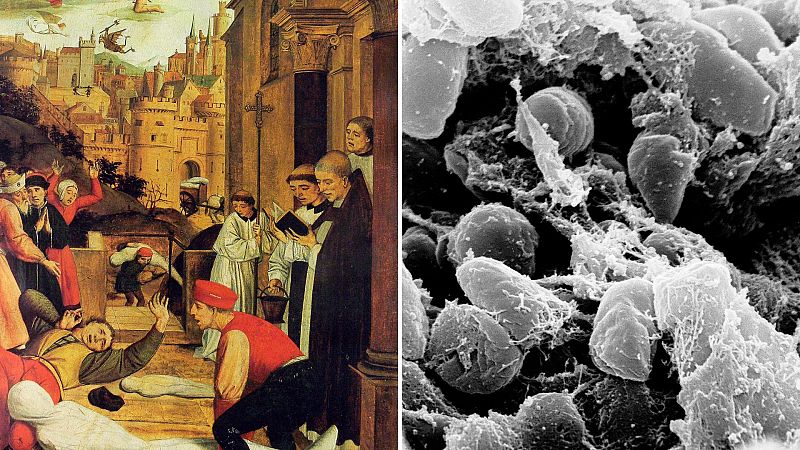

Researchers have identified traces of the Yersinia pestis bacterium in a mass grave beneath the ruins of Jerash in Jordan, providing the first direct biological evidence of the Plague of Justinian.

"For centuries, we've relied on written accounts describing a devastating disease, but lacked any hard biological evidence of plague's presence," said Rays HY Jiang, lead author of the study and associate professor with the USF College of Public Health.

"Our findings provide the missing piece of that puzzle, offering the first direct genetic window into how this pandemic unfolded at the heart of the empire".

How Yersinia pestis caused a pandemic

The Justinian Plague, which began in 541 CE, marks the world’s first recorded pandemic. Sweeping across the eastern Mediterranean and the Byzantine Empire, some historians believe it was one of the deadliest pandemics in history, resulting in the deaths of an estimated 15 to 100 million people during two centuries of recurrence.

The mystery behind the plague has now been solved: researchers believe it was caused by Yersinia pestis, the same bacterium responsible for later outbreaks, including the Black Death in 1346.

The zoonotic bacterium spreads primarily via fleas that infest rodents, particularly rats living in close contact with humans, and can also be transmitted directly between people in its pneumonic form.

Unlocking the 1,500-year-old mystery

Using advanced DNA techniques, the new study, led by an interdisciplinary team at the University of South Florida and Florida Atlantic University, examined eight human teeth recovered from burial chambers beneath Jerash’s ancient Roman hippodrome.

The DNA revealed that the victims shared almost identical strains of Y pestis, confirming the bacterium’s presence in the empire between 550 and 660 AD. The findings suggest a swift, deadly outbreak, consistent with historical accounts of mass fatalities.

"The Jerash site offers a rare glimpse of how ancient societies responded to public health disaster(s)," said Jiang.

"Jerash was one of the key cities of the Eastern Roman Empire, a documented trade hub with magnificent structures. That a venue once built for entertainment and civic pride became a mass cemetery in a time of emergency shows how urban centres were very likely overwhelmed".

A related study shows that Y pestis had circulated among human populations for millennia before the Justinian outbreak. It also suggests that later pandemics - including the Black Death and sporadic cases today - did not emerge from a single source but arose independently from animal reservoirs.

"We've been wrestling with plague for a few thousand years and people still die from it today," Jiang said.

"Like COVID, it continues to evolve, and containment measures evidently can't get rid of it. We have to be careful, but the threat will never go away".

Today