British ex-soldier acquitted of murder in 1972 Bloody Sunday massacre in Northern Ireland

A former British paratrooper has been acquitted of murder over the 1972 Bloody Sunday massacre in Northern Ireland.

The defendant is the only soldier to have been charged in connection with the shooting, in which members of the Parachute Regiment killed 13 demonstrators and injured at least 15 others.

The ex-lance corporal, known only as Soldier F, had pleaded not guilty to two counts of murder — for the deaths of 22-year-old James Wray and 27-year-old William McKinney — and to five counts of attempted murder.

On Thursday, Judge Patrick Lynch ruled at Belfast Crown Court that there was insufficient evidence to convict the veteran over the deadliest shooting in the period known as The Troubles.

However, Lynch, who presided over the non-jury trial, stressed that British soldiers that day “had totally lost all sense of military discipline".

“Shooting in the back unarmed civilians fleeing from them on the streets of a British city," he said. "Those responsible should hang their heads in shame.”

Lynch added that he could not issue a guilty ruling because the concept of “collective guilt” does not exist in the courts.

The verdict, which reflected the weak evidence prosecutors had to rely on, was a blow to families of victims who have spent more than a half-century seeking justice.

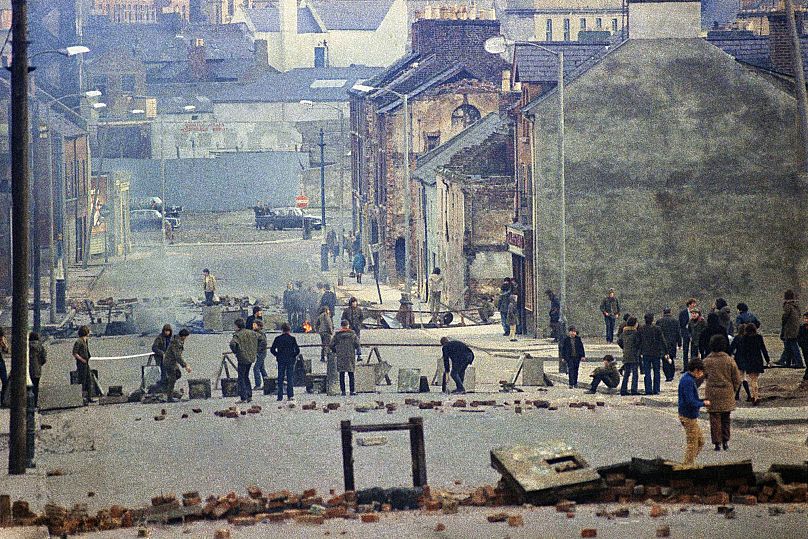

Prosecutors said that Soldier F fired at fleeing demonstrators on 30 January 1972 in Londonderry, also known as Derry.

The event has come to symbolise the conflict between mainly Catholic supporters of a united Ireland and predominantly Protestant forces that wanted to remain part of the United Kingdom.

The killings were a source of shame for the British government, which initially claimed that soldiers had fired in self-defence after being attacked by gunmen and people throwing firebombs.

While the violence largely ended with the 1998 Good Friday peace accord, tensions still remain.

Families of civilians killed continue to press for justice, while supporters of army veterans complain that their losses have been downplayed and that they have been unfairly targeted in investigations.

Soldier F, who was shrouded from view in court by a curtain throughout the five-week trial, did not testify in his defence and his lawyer presented no evidence.

The soldier told police during a 2016 interview that he had no "reliable recollection" of the events that day, but was sure he had properly discharged his duties as a soldier.

Defence lawyer Mark Mulholland attacked the prosecution's case as "fundamentally flawed and weak" for relying on soldiers he dubbed "fabricators and liars," and the fading memories of survivors who scrambled to avoid live gunfire that some mistakenly thought were rounds of rubber bullets.

Surviving witnesses spoke of the confusion, chaos and terror as soldiers opened fire and bodies began falling after a large civil rights march through the city.

The prosecution relied on statements by two of Soldier F’s comrades — Soldier G, who is dead, and Soldier H, who refused to testify.

The defence tried unsuccessfully to exclude their statements.

Prosecutor Louis Mably argued that the soldiers had, without justification, all opened fire intending to kill, and thus shared responsibility for the casualties.

A formal inquiry cleared the troops of responsibility, but a subsequent and lengthier review in 2010 found soldiers shot unarmed civilians fleeing and then lied in a cover-up that lasted for decades.

Then Prime Minister David Cameron apologised and said that the killings were "unjustified and unjustifiable".

The 2010 findings cleared the way for the eventual prosecution of Soldier F, though delays and setbacks kept the case from coming to trial until last month.

Today