Commission launches Mercosur deal ratification amid political tensions in France

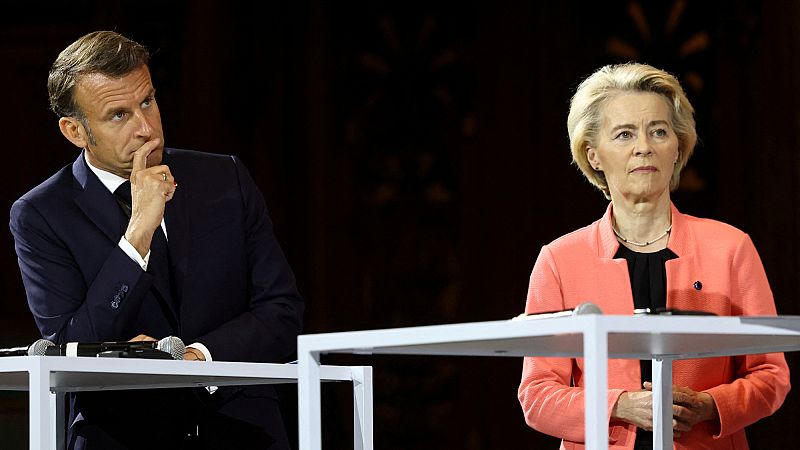

The Commission launched the ratification process for the trade agreement concluded in December 2024 with Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay on Wednesday, hoping that the most resistant member states — led by France — will ultimately give their approval.

To that end, it has met a key demand from Paris, by attaching a declaration to the agreement committing to closely monitoring potential market disruptions for EU producers of the most sensitive products, such as beef and poultry.

The deal between the EU and the Mercosur countries aims to create a free trade area between the two blocs with tariffs gradually disappearing on most products, except for some agri-products subject to quotas.

The declaration, which is expected to take the form of a legal act, will not bind the Mercosur countries, but only the Commission itself — in the hope of addressing the concerns of farmers worried about unfair competition from Mercosur products.

Under the deal reached in 2024, a market disruption can lead a country to trigger a safeguard clause that restricts imports from another country. France considered this clause insufficiently effective.

The Élysée, politically embattled as the government faces a confidence vote in the coming days, has yet to respond to the Commission’s announcement.

The Mercosur agreement is a highly sensitive issue in France — one that has, until now, united the country’s main political forces in opposition.

Commission claims implementation is 'democratic'

The deal must now be signed by EU member states, the majority of whom favour the agreement, eager to compensate for the deteriorating trade relationship with the US.

At the height of the controversy, France could count on the support of Poland, the Netherlands, Austria, and potentially Italy to form a blocking minority in the Council. But after months of painstaking negotiations over a tariff agreement with the US, that balance appears to have shifted.

Keen to see the trade deal implemented “swiftly”, the Commission has also opted to split the text into two parts: a trade component, which will go directly through the Council of the EU — where member states are represented — and the EU Parliament; and a second component, which will be submitted to national parliaments.

This process — defended by a senior EU official as “in line with the treaties” and “democratic” given that it will be examined by elected MEPs — would allow the trade part to enter into force more quickly.

A similar approach was used for the EU-Canada agreement (CETA), whose trade provisions have been provisionally applied even though the full agreement, including investment related matters, has yet to be ratified by the 27 national parliaments.

Today