France's Zucman tax: Will taxing the ultra rich really help to balance the budget?

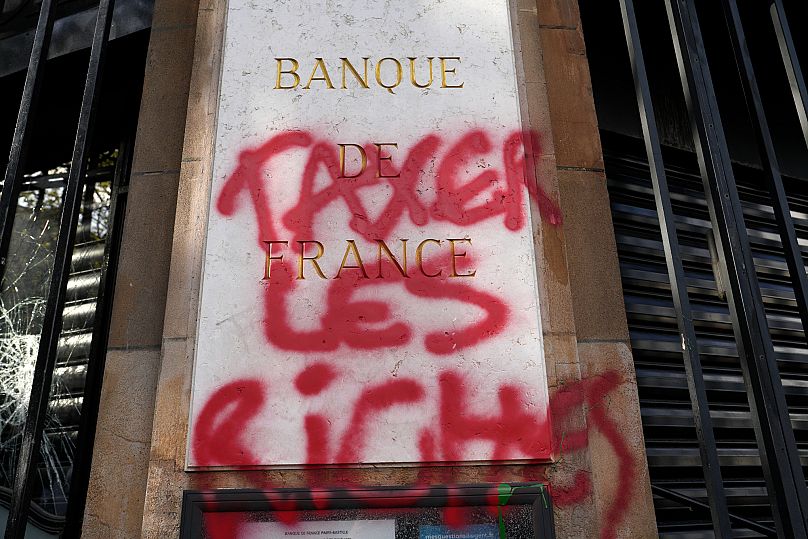

It's a subject that has caused a stir in French politics: the so-called Zucman tax.

The proposal involves levying a minimum 2% tax on top of regular income tax on individuals who have assets of more than €100 million. In France, this new tax rate would apply to roughly 1,800 people.

For its supporters, this idea represents tax justice at a time when European member states are being called on to spend more on security and defence.

Giulia Varaschin, policy adviser at the EU Tax Observatory, points out that it is not only "a very popular measure" with the public, but also "across the political landscape."

An advantage of the proposal, according to Varaschin, is that it "addresses a problem, namely that the ultra-rich pay less tax."

The Zucman tax is the brainchild of French economist Gabriel Zucman, who has advocated for a global minimum wealth tax to address the low tax burden on the ultra-rich.

He proposes to correct a form of tax inequality in which the wealthiest pay less tax than the rest of the population.

But opponents of the idea say the new tax would impact more people than just the ultra-wealthy.

"It won't just affect billionaires. We need to be aware that this tax will also affect entrepreneurs who have developed their businesses and family businesses," says Mikael Petitjean, chief economist at Waterloo Asset Management and professor at the Catholic University of Louvain.

One risk could be companies reducing their investments.

"Over the last 30 years, the 500 richest people in France have grown from 6% of the national GDP to 42% today," said Giulia Varaschin.

Replenishing the coffers without budget cuts

According to Zucman, his measure would make it possible to make up part of the French deficit without making deep budget cuts. The Zucman tax could bring in around €20 billion for the French government.

"Basically, when we talk about finding money to fill the budget, we can either reduce public spending, which would mean cutting social assistance, pensions and healthcare, or collect more money, particularly from people who don't already pay any," summarises Varaschin.

The cumulative effect at EU level would be even greater, since it is estimated that such a tax would bring in €67 billion for Member States.

But Petitjean says the figures don't add up.

"I don't think we'll come up with €20 billion. Some estimates are more like €5 billion, but I even wonder. I think it's even possible that it won't make any money at all," he told Euronews.

"There is a dynamic of behavioural adjustment that is often very much underestimated by economists, which means that people don't let themselves be taken advantage of. Strategies are used to try and avoid this tax," Petitjean said.

An additional tax also raises the threat of a tax exodus by the ultra-rich but this argument has been rejected by the European Tax Observatory.

"The data we have on capital flight following tax increases, in other words the fact that rich people leave their country after a tax rise, shows that tax exile is very, very marginal. And according to all the data we have, it has always had a negligible economic effect," Varaschin explains.

Which European countries tax their wealthy?

Out of European Union member states, only Spain has applied a solidarity tax on large fortunes for the past three years. This levy applies to net wealth of €3 million or more.

The country's finance ministry says the measure, which was originally intended only for the 2022 and 2023 tax years, has had a "beneficial effect."

However, the idea of making the wealthy taxpayers pay more is causing a stir in other European countries. Norway, which is not part of the EU, has a wealth tax of 1.1% on assets in excess of €1.7 million. The Labour Party, which won the general election earlier this month, has pledged to maintain this system.

In Switzerland, wealth is taxed, but the percentage varies from state to state. A political debate is currently underway on how much the country should tax inheritance, with a proposal suggesting to apply levy on inheritances in excess of €53 million (50 million Swiss francs) at 50%, with the aim of financing the climate transition.

Petitjean does, however, qualify these last two examples.

"Switzerland and Norway are two very rich countries with a lot of capital. In Norway, you know, you have a colossal sovereign wealth fund, and in fact they have a bit of an embarrassment of riches in Norway, and in Switzerland too", he explains.

Other member states tax very high incomes, but on specific assets.

In France, wealth tax has not existed since 2018 but has been replaced by a tax on real estate wealth. This only applies to property assets with a net value in excess of €1.3 million.

Until 2001, the Netherlands had a wealth tax. Currently, a 36% tax is applied to "notional returns" on assets. The system covers second homes, savings and shares.

In Belgium, a solidarity contribution is levied on certain securities.

In the United Kingdom, a debate is under way on the taxation of the ultra-rich whose assets exceed £10 million (€11 million).

The proposal, championed by NGOs, Labour Party officials and French economist Thomas Pikkety, envisages a 2% tax on these very wealthy individuals. The opposition Conservative Party is opposed to the measure.

Today