“The Graffiti Chronicles”: How a Ukrainian NGO is preserving everyday medieval life

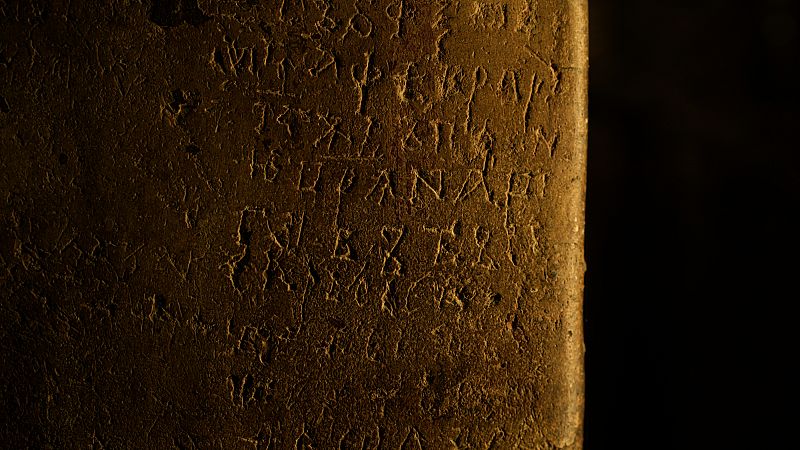

St. Sophia’s Cathedral, one of eight UNESCO world heritage sites in Ukraine, is one of the few surviving buildings from the Kyivan Rus era and one of the most important Christian shrines in all of Europe. Built in the 11th century, it preserves not only the high art of the time period, but also remnants of everyday medieval life. Namely, 7,500 inscriptions - including notes, names, prayers, and drawings - left by ordinary inhabitants of Kyiv.

“The walls of St. Sophia’s Cathedral have preserved not only thousand year-old mosaics and frescoes, recognized as masterpieces of medieval art, but also thousands of inscriptions and drawings that visitors etched over centuries,” Vyacheslav Kornienko, Deputy General Director for Scientific Work of the Sofia National Reserve, said in a press release obtained by Euronews.

“These graffiti are a vast archive of invaluable historical records, offering us a glimpse into various aspects of life in those times,” he added.

The project comes at a particularly crucial time for the fight to preserve and defend Ukrainian heritage and cultural identity. In 2024, Unesco published a list of 343 cultural sites verified to have suffered damage since the beginning of the Russian invasion. In July of this year, a Russian drone attack on Odessa damaged UNESCO-protected landmarks, such as Prymorskyi Boulevard and the Pryvoz Market, both part of the historic city center.

Geared at appealing to young people and following the growing trend of digitally preserving cultural heritage, the so-called “Graffiti Chronicles” aim to preserve the history of everyday people and highlight Ukrainian resilience.

“Since I first saw these symbols in 2021, I was fascinated by what they could tell us about our past. It was incredible to think that ordinary people like us stood in front of these walls and wrote their fears, dreams, and wishes, the same way we can stand and look at them now, a thousand years later,” Agatha Gorski, co-founder of the shadows project, said in the press release.

“Our team wanted to find a way to bring these unique and important pieces of history out of the shadows, inviting Ukrainians to discover for themselves what these hidden gems can tell us about our heritage,” she added.

At the next stage of the project, QR codes will be installed next to the graffiti on the walls of the cathedral museum, allowing visitors to access the digital archive and additional information about the works from their phones.

“They do everything possible to strip us of our historical memory”

For Ukrainians, now in the third year of full-scale war, the ability to digitize their history and culture has become relevant as ever.

“Digitized documents, objects of material heritage, and cultural monuments help preserve their memory in the form of a digital copy, even when the original no longer exists,” Dr. Vyacheslav Kornienko said in an interview with Euronews.

“This has become especially relevant for us during the war, as Russian aggressors deliberately destroy cultural sites and loot museums - in other words they do everything possible to strip us of our historical memory,” he added.

While the process of digitally archiving cultural artefacts and documents is an important step, he admitted that more work is needed to complete the preservation process and avoid the loss of cultural heritage and historical memory.

“I believe that the best option is to combine both: digital copies should be created separately (like a deposit for safekeeping), but these copies should then serve as the basis for scholarly research, including monographs, catalogs, and articles that feature these heritage items,” he told Euronews.

The digital versions of the graffiti at St. Sophia’s Cathedral are not simply scans or photos, but rather 3D visualizations of it, preserved in video format. They also include information about the symbols and their meaning which was not previously available in English.

Fighting Russian misinformation

For Ukrainians, preserving cultural heritage, even from the Medieval era, can help to fight disinformation in the modern day. This includes disinformation spread by Russia in order to justify its invasion, such as the narrative that Russia and Ukraine were one during the Kyivan Rus period.

“I think this topic of the Kyivan Rus is a highly contested aspect and one that is a huge part of Russia's disinformation operations and how it tries to weaponize culture,” Agatha Gorski, who grew up across from St. Sophia’s, said in an interview with Euronews.

“This is one of the first things that Putin said before the invasion, one of the key arguments, [he said in a speech that] Russia and Ukraine are one people,” she added.

“He very often likes to use this claim and go back into the times of the Kievan Rus, and use it to justify the invasion, and to justify the fact that Ukraine is not an independent nation, so for me, it was really important to also take this time period, because it's super crucial to us, and super crucial to our knowledge gaps, to fill that in,” she added.

More than this, the lives of people from centuries ago can also serve as a symbol in an of itself for the resilience of the Ukrainian people and their culture, something that the Shadows Project has seeked to emphasize in this project, as well as in their other work.

“For me, any kind of history starts with people. In people's everyday lives and in experiences because this is really what can tell us the most. This is also again kind of the parallel for me with the shadows project where for us like we really try to tell the stories of people and we try to really make history accessible, make history alive, and tell it through the experiences of others,” Gorski told Euronews.

Today