Newly discovered document adds evidence that Shroud of Turin is not Jesus' crucifixion shroud

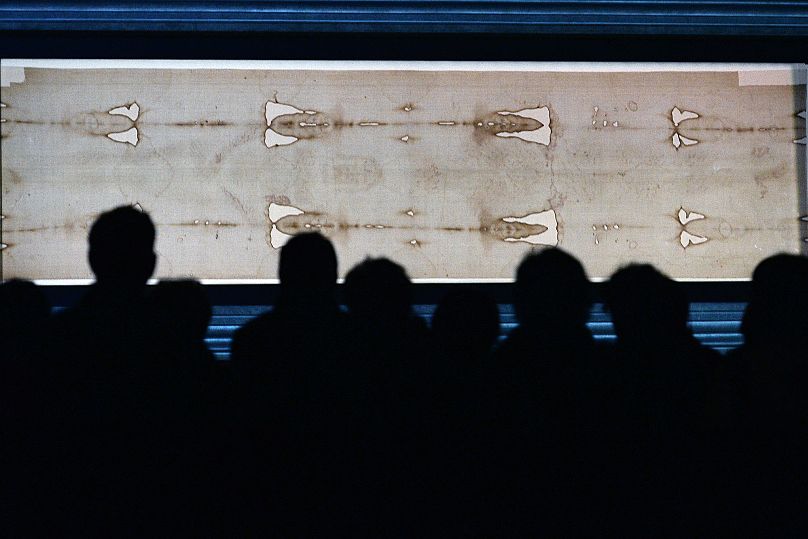

The Shroud of Turin is one of the most treasured ancient artefacts, attracting countless tourists to the Italian city - despite the fact that the Cathedral of St. John the Baptist in Turin only publicly displays it on special occasions.

Also known as the Holy Shroud, the linen cloth bears the faint image of the front and back of a naked man. Believers have venerated it for centuries as Jesus’ shroud – upon which his image was imprinted after the crucifixion.

People have questioned its genuineness since it first emerged in 1354, and Vatican authorities have repeatedly gone back and forth on whether it should be considered as the true burial shroud of Jesus Christ. Additional research over the years has added evidence that it may not be authentic.

Now, a newly discovered medieval document adds further proof that the shroud is a fake.

Published in the Journal of Medieval History, the findings reveal the earliest known written evidence dismissing the relic.

Indeed, the previously-unknown document, which dates from the 14th century, offers one of the oldest dismissals of the famous 14-foot cloth and stands as the oldest written evidence known to date. The previously known oldest account was a letter written in 1389 by the Bishop of Troyes, Pierre d’Arcis, which also denounced the Shroud as a fraud.

The newly-discovered written document reveals that a highly respected French theologian, Nicole Oresme (1325-1382), described the cloth as a “clear” and “patent” fake - the result of deceptions by “clergy men” in the mid-12th century.

Oresme writes: “I do not need to believe anyone who claims ‘Someone performed such miracle for me’, because many clergy men thus deceive others, in order to elicit offerings for their churches.”

“This is clearly the case for a church in Champagne (the French region where the shroud was first uncovered), where it was said that there was the shroud of the Lord Jesus Christ, and for the almost infinite number of those who have forged such things, and others,” he wrote.

Oresme, who later became the Bishop of Lisieux, France, was an important religious figure in the Middle Ages, well-regarded for his rational explanations for so-called miracles.

“What makes Oresme's writing stand out is his attempt to provide rational explanations for unexplained phenomena, rather than interpreting them as divine or demonic,” said Dr Nicolas Sarzeaud, historian at Université Catholique of Louvain, Belgium, and lead author of this new study.

“This now-controversial relic has been caught up in a polemic between supporters and detractors of its cult for centuries,” continued Dr Sarzeaud. “What has been uncovered is a significant dismissal of the shroud... This case gives us an unusually detailed account of clerical fraud.”

Today