'Surrounded by Criminals': The photographer capturing the hidden language of Soviet prison tattoos

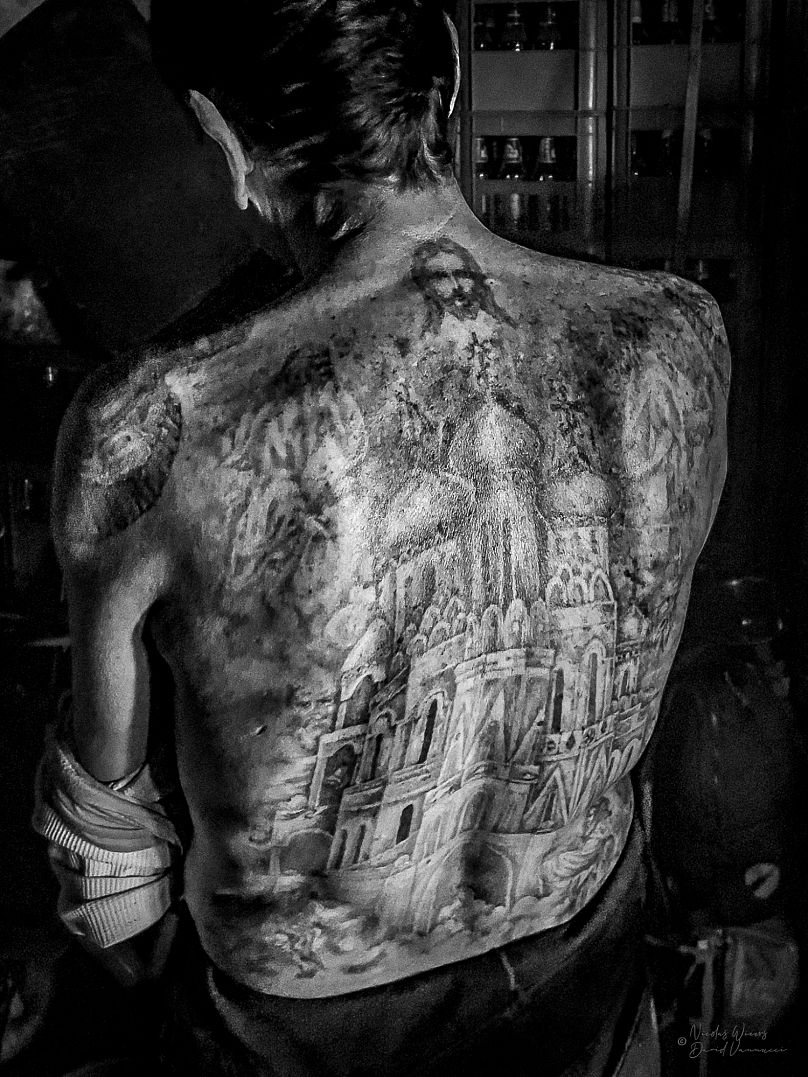

Black-and-white faces. Eyes that have witnessed decades of prison life and streets ruled by shadow codes. Bodies inked with stars, spiders, cats and cathedrals - symbols of rank, loyalty and defiance.

A new city-wide exhibition exhibition in Brussels, Surrounded by Criminals, invites visitors into the hidden underworld of the Vory v Zakone, the post-Soviet “thieves in law” brotherhood who once controlled the criminal networks of Stalin-era gulags.

Behind the lens is Belgian artist and filmmaker Nicolas Wieërs, who spent several years in Moldova and Transnistria photographing these men. Earning their trust, he documented a little-known subculture defined by tattoos, hierarchy and survival. Once revered as “gods” of the Soviet underworld, many now live on society’s margins, trapped in cycles of poverty, addiction and crime.

"I began to question whether there’s a kind of hypocrisy in society. Through their tattoos, I could explore our collective point of view on crime and punishment," he told Euronews Culture.

Through portraits, testimonies and an immersive setup of music, film and drawings, Wieërs examines their tragic yet fascinating lives - while confronting ideas of justice, morality and social hypocrisy. His work contrasts the visible, tattooed ex-prisoners with the invisible crimes of the powerful - from politicians to white-collar elites - shielded by wealth and influence.

Spanning six unique locations across Brussels, from tattoo studios to a renovated, former stock exchange building, the exhibition runs until 9 November 2025.

Euronews Culture sat down with the photographer ahead of the show to discuss the process, his encounters with these men, and the aims behind the project.

Euronews Culture: So, in your own words, how would you describe this project?

Nicolas Wieërs: I began the project out of curiosity about the meaning behind the tattoos of the Vory v Zakone - a criminal fraternity that existed during the Soviet era, before the collapse of the USSR in the early 1990s.

At the time, I was living in Moldova, which gave me the perfect opportunity to meet these men daily. I began entering their world, creating a network, building trust with a few of them. At first, my interest was mainly in the tattoos themselves - the meanings behind each symbol.

But soon I realised there was much more history behind every tattoo. The tattoos of the Vory v Zakone told the story of their lives. When they started to talk about their tattoos, the project became something far bigger than just tattoos - it became about humanity, morality and how we view criminality itself.

Many of the men I met had spent around 30 years in prison - sometimes for almost nothing. They served their time, but once free, they were still outcasts. Many no longer spoke the local language - they spoke prison slang. They had no real place in society anymore.

So I began to question whether there’s a kind of hypocrisy in society. Through their tattoos, I could explore our collective point of view on crime and punishment. Because when you look at the state of the world, it’s strange that we continue to condemn people who are already, in a sense, nearly dead - living on the streets, covered in tattoos that mark their criminal past - while, at the same time, we follow rules and systems created by other kinds of criminals. That’s why I titled the project 'Surrounded by Criminals' - because the real criminals aren’t always who we think they are, and they’re not always the ones we can see.

How do the men you photographed - once considered 'gods' in prison with a certain status - reflect on their experience of going from power to poverty and social exclusion in today’s society?

First of all, the guys I met were not the big bosses of the fraternity. They were the smaller members, each with their own specialty. A few of them, for example, were really the tattoo guys in jail. Some of them were bank robbers and thieves. I wasn’t interested in the big bosses who are still continuing their business.

From their feedback about the past, they were really living in a parallel world, with their own code, rules and their own way of speaking. They had very specific slang. So coming back to society was incredibly difficult for them - they didn’t understand the social world outside their bubble. When I met them on the street in their squats, it was clear how hard it was for them to continue their lives normally.

Regarding their tattoos, how do they talk about them today? Do they still see them as symbols of pride, or are they more of a burden?

They are still proud of their tattoos because they’re part of their life. However, they don’t show them publicly. In societies like Moldova, Ukraine, Kazakhstan - this geographic region - tattoos are still associated with criminal subculture, unlike in the USA, which has embraced the sort of punk aesthetic. For that reason, they prefer to hide them.

The tattoos originated in prison and represent rank, status, identity and loyalty, right? Could you talk about the symbols you saw most often and the recurring tattoos that appeared frequently?

It starts with a type of juvenile ring - this is the first step to integrate into the fraternity. Juvenile rings indicate that someone began very young in jail, often around 14 or 15. Their first tattoos usually appear on the fingers as these rings, marking their early status in prison.

Another very common tattoo is the star, usually on the shoulders or underneath. This symbolised defiance against the communist authority - they would never kneel before government officials. Today, this meaning no longer exists, but back then, it was part of the “law” in their parallel society. Even holding a normal job outside jail could be unacceptable - they lived in their own social bubble.

After the rings and stars, there’s the spider on a web tattoo, which comes with dots. The direction of the spider has meaning: if it’s climbing, it means they are still active in crime; if it’s going down, it means they’ve decided to stop. Then there were tattoos indicating rank - like military-style ranks on the shoulders - showing status in jail.

There were also tattoos referencing the Orthodox Church, often on the back. The number of crosses indicated how many years they had spent in jail - the more crosses, the more respected they were.

Tattoos also gave them a type of freedom within jail. Freedom could be something simple, like being allowed to play chess, but it was meaningful. Being part of the fraternity was crucial for survival.

Why do you think it’s important to document this subculture before it disappears?

Because it's part of history. Every country is different, with its own history and rules. It’s important to know your roots - whether you’re proud of them or not, at least to understand your own patrimony. As a European living in Moldova, I was amazed by this subculture.

I don’t have anything like it in Belgium. That kind of subculture doesn’t exist there. Across Europe, it’s hard for people, even Moldovans, to fully understand or appreciate it, because they didn’t live with it daily.

Did you ever feel intimidated or scared when photographing any of your subjects?

Yes, a few times. But it wasn’t just me - because to meet them and understand their conversations, mostly in Russian slang, I had to work with an interpreter. I had to rely on fluent, native Russian speakers.

Entering their world - you’re immediately exposed to discussions about drugs, knives and violence. It’s a world of poverty and danger, completely outside my own bubble. As a young European photographer, it could definitely feel intimidating. But ultimately, nothing ever happened to me. You have to accept it and focus on taking the best photos possible.

Has working on this project changed your perspective on crime, justice and forgiveness in society?

I wouldn’t say it changed my mind, but it reinforced my perspective. What struck me was how humble and educated these people were. It’s paradoxical - they had a lot of time to read in jail. And they were very knowledgeable on their subculture. They could explain the meaning behind the tattoos, why certain tattoos were done or not done. It was like opening a living dictionary.

My point of view about criminality didn’t change - they were criminals but they paid the price. Many spent decades behind bars. I met people who arrived in jail at 14 and spent decades cycling in and out. Yet there were rules within their world: for instance, it was forbidden to commit rape, to steal from an elderly woman, and members were expected to help one another. It was a different kind of criminality than what we see on the streets today .

So I was really impressed by their mentality. Many were older men, but they were good people - they didn’t live like chaotic street criminals. They had learned a lot within that system. That’s why I’m proud to share this part of their culture with my audience in Brussels.

Can you talk about why you chose to shoot in black and white and what you were aiming to capture in your photographs?

For me, photography is about framing, meeting people, networking and sharing emotion. My approach is basically street documentary. I’m not a big fan of technology. I prefer to go to a subject with minimal equipment. I wanted to capture life as it happened.

That’s why all the photos in this exhibition are truly documentary. I would take a photo, then move on, maybe ask for another contact and continue. For me, photography has to stay simple - it has to be done in the moment itself.

The photos were all taken in colour, but I chose black and white because in these social bubbles, colour doesn’t matter - the people are at the end of their own path, and colour is irrelevant to their world. I want the audience to focus on the face, the eyes, and the tattoos, without being distracted by colour.

Finally, going back to the theme of the exhibition, what do you hope people take away from this project?

The society we live in is very complicated, very black-and-white - or Manichean, as we say in French - which means seeing things strictly as good or evil. What I wanted to do with this photography exhibition is add some nuance. When people see someone labeled as a criminal, there’s often a deeper story behind them.

Some of these people have already paid their dues. They deserve respect or at least to be included in society. The goal of this project is to bring a little nuance to how we think about criminality, to show that it’s not always as simple as it seems.

'Surrounded by Criminals' is on display until 9 November 2025 at the following locations: AGORA Room at the Bourse, the NATHALIE AUZEPY L’Impératrice Studio, the tattoo parlours MUE Tattoo Shop and Inksane Tattoo & Piercing, Le Poste - a creative hub housed in the former barracks on Place du Jeu de Balle - and the Brussels Tattoo Convention at Tour & Taxis.

Today