Almaty Museum of Arts opens its doors in Kazakhstan’s cultural capital

The long-awaited opening of the Almaty Museum of Arts marks a milestone in the region’s cultural life.

Founded by businessman and philanthropist Nurlan Smagulov, it showcases more than 700 works from Kazakhstan and Central Asia, alongside pieces by leading international artists.

With its diverse range of media, genres, and perspectives, the museum aims to serve as a hub for contemporary art in Central Asia.

Almaty Museum of Arts. Photo: Euronews.

The museum sits at the foothills of the Tian Shan mountains and stands as a work of art in its own right. Designed by British firm Chapman Taylor and completed over three years, the 10,060-square-meter complex consists of two intersecting wings — one clad in Jura limestone, the other in aluminum — symbolising Almaty’s mountainous landscape and urban environment.

Architecture as Art

Art begins before visitors even step inside. Outdoors, large-scale installations welcome guests and set the tone for the experience ahead.

Spanish visual artist, sculptor and designer Jaume Plensa’s NADES (2023) — a 12 metre portrait of a young woman with closed eyes and a traditional Kazakh braid — offers a moment of calm amid the city’s urban flow.

British-Nigerian artist Yinka Shonibare’s Wind Sculpture (TG) II (2022) offers another nod to Central Asian traditions, where scarves hold cultural significance. The 12-metre high work takes the form of a wind-blown aluminum scarf painted in vibrant Ankara-inspired patterns, reflecting on layered cultural identities and colonial legacies central to Shonibare’s practice.

Berlin-based artist Alicja Kwade’s Pre-Position (2023), inspired by Kazakhstan’s Torysh Valley and its surreal spherical rock formations, combines stone spheres and steel forms to evoke celestial systems and ancient astronomical tools — a meditation on time, gravity, and universal connection.

Qonaqtar: Guests of the Steppe

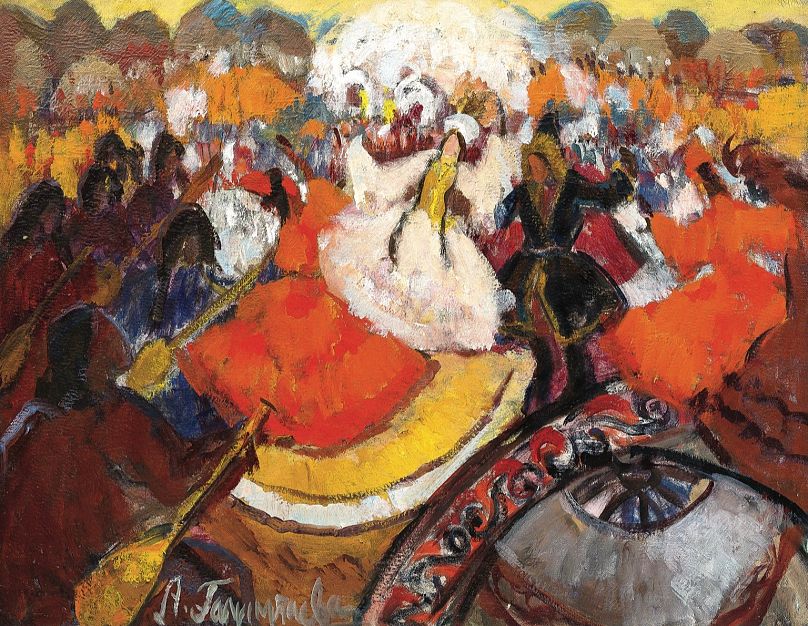

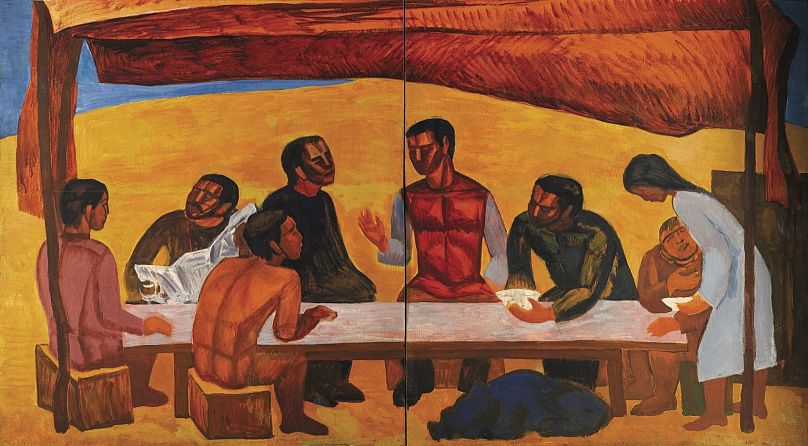

The Almaty Museum of Arts opened with two exhibitions, the first titled Qonaqtar — “Guests” in Kazakh. Centered on artists of the 1960s, the show begins with works portraying nomadic culture, daily rituals, food, and festive gatherings. Highlights include Baursaks (1993) by Bahtiar Tabiyev, showing a woman frying traditional dough, and Aisha Galimbayeva’s Shepherd’s Feast (1965).

As visitors move deeper into the hall, the exhibition turns toward more complex reflections, juxtaposing the weight of Soviet restrictions with the richness of Central Asia’s artistic heritage.

At its core is Salikhitdin Aytbayev’s photograph On Virgin Soil. Lunchtime (1960s), which addresses the Virgin Lands campaign (1954–1965) — a Soviet effort to plough vast steppe regions to boost grain production, marked by labour enthusiasm, infrastructure building, and mass migration into the region.

“If Aisha Galimbayeva is my starting point, then this is the anchor here,” explains Inga Lāce, the museum’s chief curator. “It talks about the moment when migration happens and it totally changes the population of the whole country. And that also opens up other stories of what else happens in the steppe on the land.”

Across paintings, graphic works, sculpture, and contemporary practices, the exhibition also explores themes of labour migration, identity, displacement, and belonging.

I Understand Everything: Almagul Menlibayeva’s Retrospective

The museum also presents I Understand Everything, the first retrospective of Almagul Menlibayeva, a multidisciplinary artist whose practice spans painting, textiles, performance, photography, film, and new media.

Known for blending Eurasian myths, shamanistic imagery, and post-Soviet realities, Menlibayeva has developed what she calls a personal and political “cosmology” that examines identity, memory, and cultural resilience. Her works have been exhibited internationally, including at the Venice Biennale and major museums in Europe, Asia, and the United States.

“We are so glad to finally have a space where we can truly think,” Menlibayeva says. “It feels like a temple of art — and artists have so much to share. This year I’ve had many exhibitions in Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Bangkok. Everywhere, people are deeply curious about Kazakhstan, about Central Asia. We have the perspective of looking through a post-socialist lens. We are multidimensional.”

Curated by Gridthiya Gaweewong, Artistic Director of the Jim Thompson Art Center in Bangkok, the exhibition unfolds in two chapters. The first (September 2025 – January 2026) revisits the Kazakh steppe, the Aral Sea, and the Semipalatinsk nuclear test zone, culminating in the multi-channel installation Kurchatov 22 — named after the secret town in Kazakhstan that served as the center of the USSR’s nuclear weapons program. The second (opens in February 2026) turns to Kazakhstan’s geopolitical terrains and sites of memory, featuring works on Stalin-era labor camps and women’s agency along the Silk Road.

International Perspectives

Alongside its Kazakh and Central Asian collections, the museum dedicates several rooms to leading international artists.

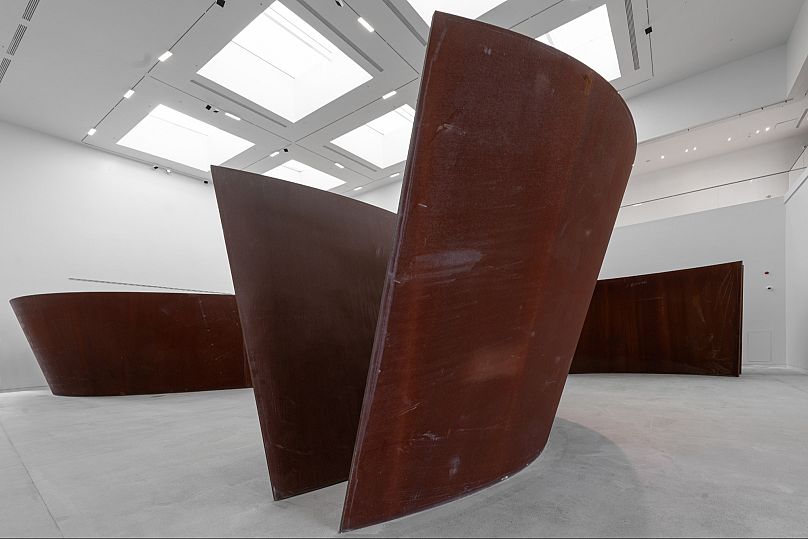

American sculptor Richard Serra’s Junction (2011) — the last large-scale work relocated with his approval before his passing — envelops viewers in vast curving steel forms that redefine the experience of space. Inside the long steel labyrinth, every step produces a heavy echo against the walls, amplifying a sense of weight and pressure.

In the room of German artist Anselm Kiefer, the scent of charcoal fills the air. His installation Questi scritti, quando verranno bruciati, daranno finalmente un po’ di luce, (2020–21) — titled after writings by Italian philosopher Andrea Emo — combines oil on canvas with burnt books and metal wire, evoking destruction and renewal.

Two additional rooms present iconic works of contemporary art: Yayoi Kusama’s Infinity Mirror Room: LOVE IS CALLING (2013), an immersive environment of light, pattern, and poetry, and Bill Viola’s Stations (1994), a meditative video installation on transformation, inspired in part by Sufi philosophy.

Looking ahead, the museum plans to rotate its collection and stage more solo exhibitions, while partnering with international curators and institutions. With workshops, education programs, and a conservation lab in development, it aims to grow into a vibrant hub for art and dialogue in Central Asia.