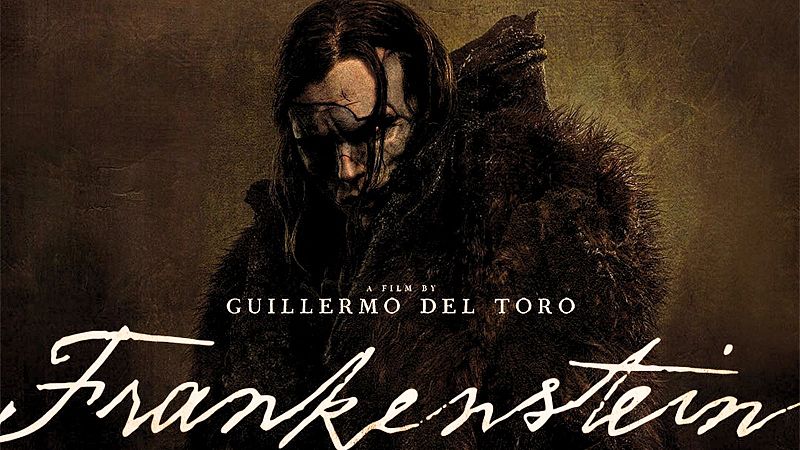

Euronews Culture's Film of the Week: ‘Frankenstein’ – The film Guillermo del Toro was born to make

Frankenstein has been a long time coming for Guillermo del Toro.

The visionary filmmaker and lover of misunderstood monsters recently shared at the Lumière Film Festival that he was seven years old when he saw James Whale’s 1931 Frankenstein on TV after a family trip to mass.

The impact was immediate.

“When I saw Boris Karloff, I understood religion in that moment,” he said. “I understood Jesus, ecstasy, the immaculate conception, stigmata, the resurrection... I understood that I had found my messiah. My grandmother had Jesus. I had Boris Karloff.”

The impact lasted and set him on a path to becoming the filmmaker he is today.

Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus” is the story del Toro been telling his whole life, ever since his first film Cronos in 1992.

From the cure to an illness taking on a life of its own in Mimic (1997) to the prodigal father / imperfect child dynamic inherent to Hellboy (2004), the Gothic romance of Crimson Peak (2015) to the vilified monster seeking human connection in The Shape of Water (2017), and even the creator / creation core of Pinocchio, Shelley’s novel has always been an intricate part of del Toro’s art.

Now, the man who has been telling humanist monster stories and tales of outcasts for as long as he’s been making movies finally releases his passion project, something which can be considered the culmination of a life’s work.

However, passion projects are notoriously tricky, with lifelong visions often crumbling under the weight of decades-long dedications, failing to arrive fully formed on the screen.

“So you think your little Frankenstein’s got the better of you?” asks F. Murray Abraham’s Dr. Gates to Mira Sorvino’s Dr. Tyler in del Toro’s Mimic.

28 years later and the same question stands: Has Frankenstein gotten the better of the 61-year-old director wishing to honour the obsession of a seven-year-old scamp discovering his messiah?

Guillermo del Toro’s Frankenstein begins in 1857, in the Arctic, as a boat full of sailors is trapped in the ice. The crew find Dr. Victor Frankenstein (Oscar Isaac), seemingly left for dead on the ice. He tells the captain (Lars Mikkelsen) his story: how the death of a young boy’s mother left a hollowed-out universe and a permanently dark firmament, leading a repressed child to become a doctor obsessed with conquering death. From the beginning, Victor became a man with little interest in life; he is man seeking to possess power over it.

But the Creature (Jacob Elordi) is still on the ice... And he's coming.

What follows is del Toro’s personal take on Shelley’s immortal work: faithful in parts, divergent in others, and always devoted when it comes to the original tone. While the director adds characters (Christoph Waltz’s arms manufacturer and benefactor Harlander) and explores its own treasured themes and tics (generational trauma; lapsed Catholicism; washing your hands before you go to the bathroom as a mark of villainy), he celebrates the emotional charge at the heart of “Frankenstein”.

His adaptation is a still the tale of an egotistical scientist playing God but also a story about storytelling, about how imperfect men become their tyrannical fathers, and most of all, a Miltonian tragedy about what it is to be human – blessed and cursed with “merciless life”. Which is fitting, since “Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus” begins with a title page with an epigraph from “Paradise Lost.”

“Did I request thee, Maker, from my clay / To mould me Man? Did I solicit thee / From darkness to promote me?”

To better honour Shelley and the pain transmitted from one generation to the next, del Toro wisely – but unevenly - splits the narrative between the perspective of Victor and his Creature. We get the scientist’s version of events – brilliantly performed by Isaac, who ups his flair for the theatrical - abruptly followed by the first-person retelling from the monster himself.

Whereas the monster has so often been cinematically encoded as a pathologically violent creature whose otherness is a threat, Shelley’s 1818 novel gave the Creature a voice. Del Toro elects to do the same, seeing humanity in a creation so often made monstrous on a visual and behavioural level on the big screen. As is the director’s way, he reverses the imposition that those who are different and deemed abnormal should be pushed to the outskirts of society – and indeed, existence - by heartless definitions seeking to control the things we fear. Instead of the groaning and bolted green lump that has permeated popular culture, del Toro makes his Creature function as both a feeling person and a mirror held up to the failures of humanity. Our refusal to embrace acceptance. Our negligence of care. Our failure to forgive.

Freed from nonverbal grunting, Elordi gets to shine as an evolving soul. Rejected by his creator with the same cruelty Victor was treated to at the hands of his authoritarian father (Charles Dance), Elordi injects pathos, child-like gentleness and hulking power into his commanding performance. Previous Frankenstein’s monsters were pitiable as ostracised monsters, but the Australian actor adds a soulfulness to the character that reinforces the brutality of being fated into eternal life without companionship. His scenes with Elizabeth (Mia Goth), Victor’s stepsister who feels empathy for the monster and who desires her own freedom, are brief but particularly beautiful. Her presence, while frustratingly brief, allows for a religious motif of complimentary yet clashing forces to form, wherein Victor is the Father; the Creature is the Son; and Elizabeth becomes the Mother Mary.

Considering the themes of sin and redemption, it’s a shame this (un)holy trinity isn’t given more screentime. Indeed, Goth’s character, who gets the film’s wisest and most romantic line (“To be lost and to be found, that is the lifespan of love”), is reduced to the role of a woman completely exhausted with the hubris of men, and deserved more. Like Elordi’s POV segment in the second “half” of the film, it’s a shame these elements weren’t more fleshed out.

A further pity is that there were reportedly plans for del Toro’s Frankenstein to be two films: Victor’s version of events for the first; the second told from his Creature’s.

Still, the way the director manages to focus on the achingly emotional heft of the source material within a staging that is nothing short of operatic is an achievement of no small size.

Speaking of scale, Frankenstein is an epic tragedy of emotions matched by its craft.

On a technical level, it’s no hyperbole to say that this is one of the most sumptuous looking films you’ll get to see all year. For those lucky enough to catch it during its all-too-brief release in select cinemas, do not hesitate, as everything from the costume design (Kate Hawley), the production and set design (Tamar Deverell and Shane Vieau) to DoP Dan Laustsen’s craft is astonishing to witness.

The sets in particular, all unmistakably del Toro decors and featuring visual callbacks for those familiar with the director's work, provoke the intense desire to explore their intricate little details. The abandoned irrigation plant which becomes Victor’s lavish laboratory, complete with cogs, a stone Medusa head and plenty of dead soldier limbs, is a world-building marvel that will leave you gobsmacked.

It’s a cruel shame that most audiences will get to witness this visual feast on small screens, as a film this stunning deserves a big screen – reigniting the argument that Netflix desperately needs to rethink its streaming-only strategy and allow for broader theatrical windows.

After 207 years since the novel and more than 60 feature films based on the source material, the story of Dr. Frankenstein and his monster continues to fascinate and ask the still urgent question: What is it to be human?

Del Toro appreciates this and through his signature Gothic sensibilities and singular craft, full of haunting Romantic beauty and welcome smatterings of body horror, answers with great heart.

While his version of "Frankenstein” may not be one of his greatest achievements, his reverence to the source material frequently muting some of the unexpected and strange flourishes seen in Cronos, The Devil’s Backbone or Pan’s Labyrinth, it certainly makes a lot of literature and film lovers’ dreams come true. To get to watch Guillermo del Toro, whose films have shown that humans harbour monstrosity and monsters overflow with humanity, finally come full circle with his take on the story that started it all can only be a joy. He’s managed to tame the passion project beast and made his childhood dream come true.

There’s little doubt that the seven-year-old who found his messiah in Boris Karloff would be proud of the adult who did not let Frankenstein get the better of him.

More than that, pint-sized Guillermo would’ve loved this operatic and sweepingly emotional tale with a heart that will break, “yet brokenly live on”.

Frankenstein is out in select theatres on 17 October, followed by a global streaming release on Netflix on 7 November.

Today